Case Study

World Bank

Investigating the co-existence of a mega-mine and traditional nomadic herding in Mongolia's Gobi Desert.

This was an interdisciplinary research project, funded by the World Bank and led by Dr Troy Sternberg and Dr Ariell Ahearn from the University of Oxford. Jerome Mayaud worked as a research assistant and methodological expert.

The project centred on the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mega-mine in Khanbogd Soum, Mongolia. The core objective was to assess the environmental changes and socio-economic implications of large-scale mining on traditional nomadic pastoralism and local livelihoods.

The research was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The primary goals of the project were to:

Provide an integrated assessment: Combine quantitative physical data (on pasture, water and dust) with qualitative social science data (interviews, perceptions, participatory mapping) to holistically assess the impact of the mega-mine.

Resolve disputes and build trust: Use our independently gathered evidence and participatory mapping to increase transparency and trust in the dispute resolution process between the extractive industry and the local community.

Inform Policy: Provide an effective approach to address the roles of herders, government, and the mine in supporting the future of pastoralism in the region.

Project goals

We conducted an intensive fieldwork campaign in the Gobi Desert using novel methodologies, to collect a variety of socio-economic and physical environmental data:

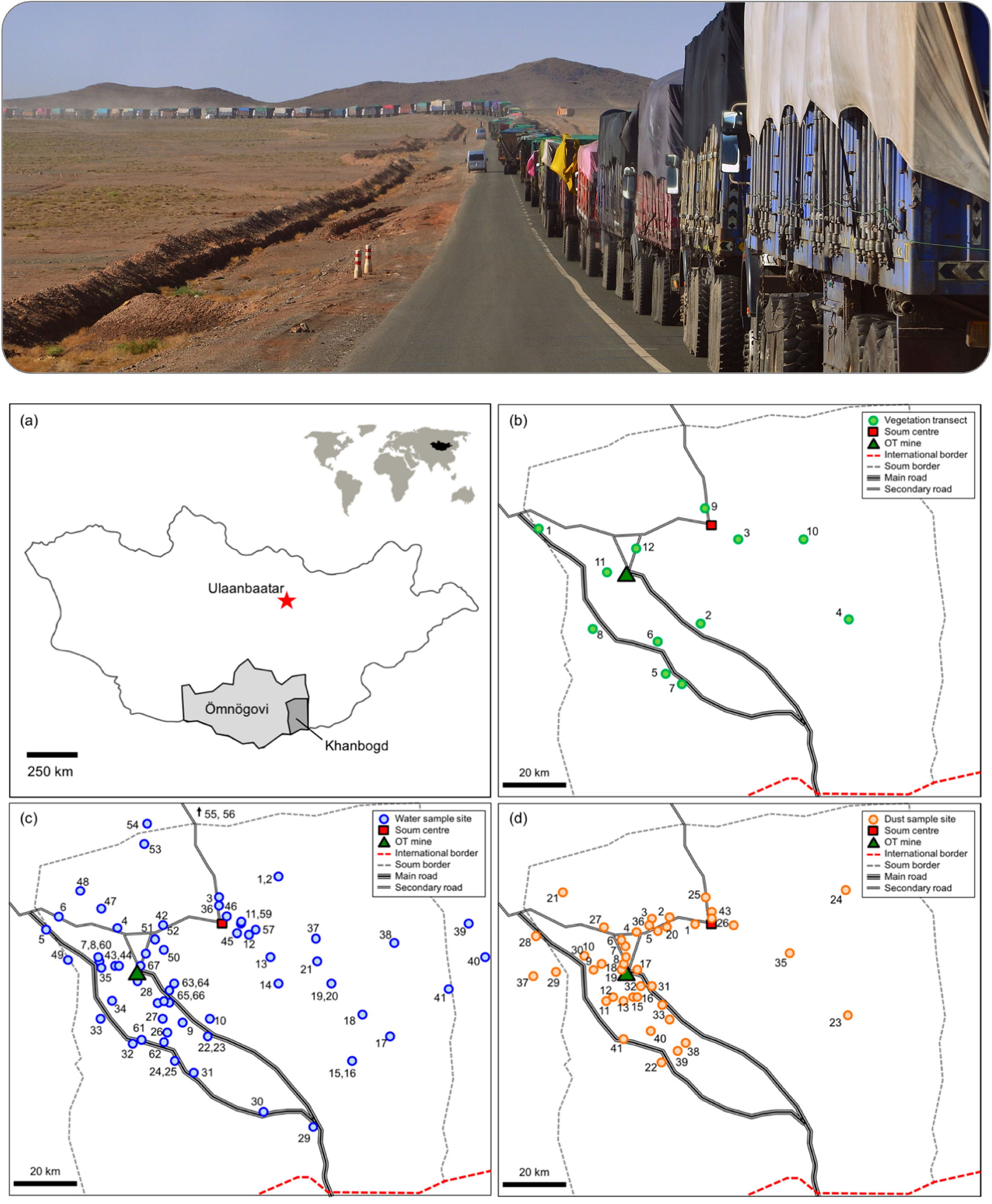

Physical data collection included vegetation transects (assessing cover near water sources), water quality and access surveys (at 67 sites, noting unusual locked deep wells), and dust trap deployment (43 sites, supplemented by GIS analysis of MODIS AOD data).

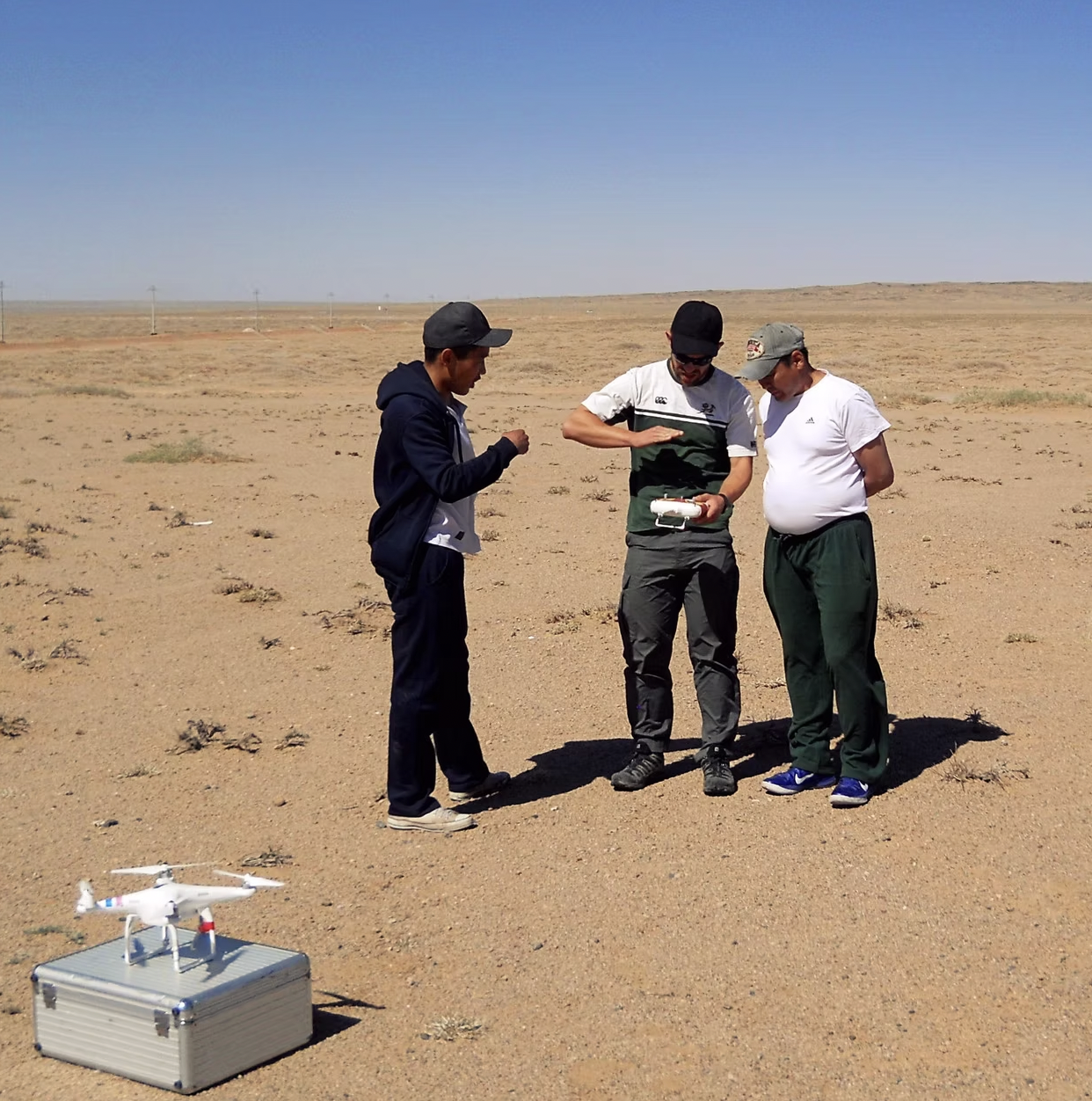

Social data collected via 106 herder household interviews and 53 environmental surveys to assess perceptions, changing land-use practices, and socio-economic dynamics, including participatory mapping using drone imagery.

Approach

Co-existence is possible: Contrary to common narratives, our study concluded that mining and herding can, and do, coexist in Khanbogd Soum.

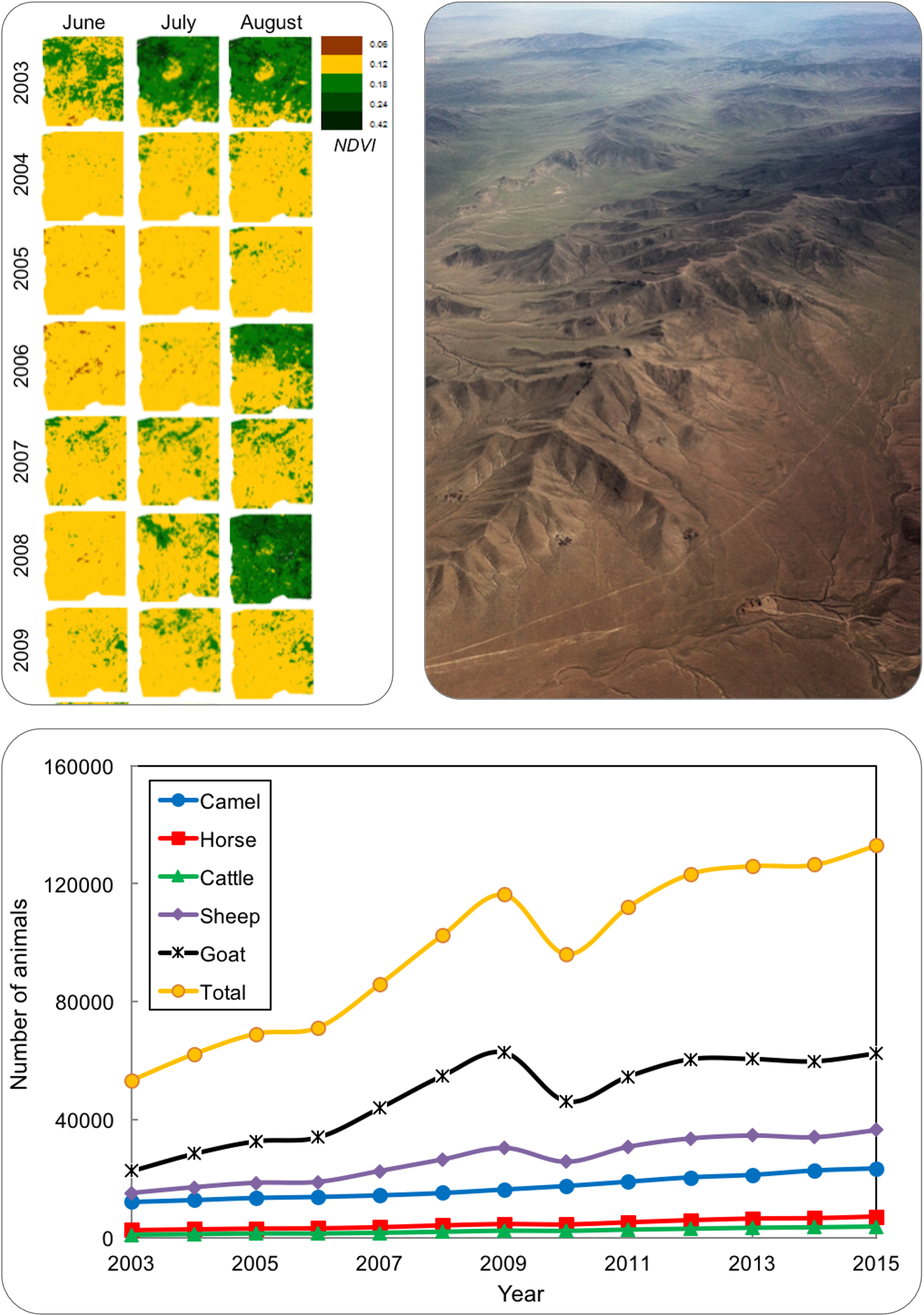

Impact of climate vs the mine: Macro-scale environmental changes like pasture coverage are primarily driven by interannual precipitation variability, not mine activities. However, there was evidence the mine did impact local pressure points like water access and dust levels.

Water access challenges: Herder perception overwhelmingly blames the mine for water shortage, but we identified other driving factors, including high livestock numbers, slow well recharge, and the unusual presence of locked deep wells (85% of surveyed deep wells were locked).

Drone-enabled participatory mapping works: Drone imagery served as direct evidence for land degradation and, critically, engaged herders in the process, boosting transparency and trust in the research results.

Livelihood transformation: Herder livelihoods are transforming due to a confluence of factors, including increased livestock numbers (which have doubled since 2003) , loss of customary land access due to new infrastructure (roads, fences) and job opportunities at the mine. These challenges are often exacerbated by ineffective local government in managing land and water disputes.

Key results

Our findings stress the need for interdisciplinary and participatory methods to: (a) establish accurate baseline dynamics for resource management, and (b) do so in a way that engages local herder stakeholders.

We advocated that the local and national governments must work together to establish effective environmental practices and safeguards to support the rural population. After all, herders will continue to be the long-term stewards of the Gobi after resource extraction is complete.